KH6MG/ZK1 DANGER ISLAND 1958 INTERNATIONAL GEOPHYSICAL YEAR

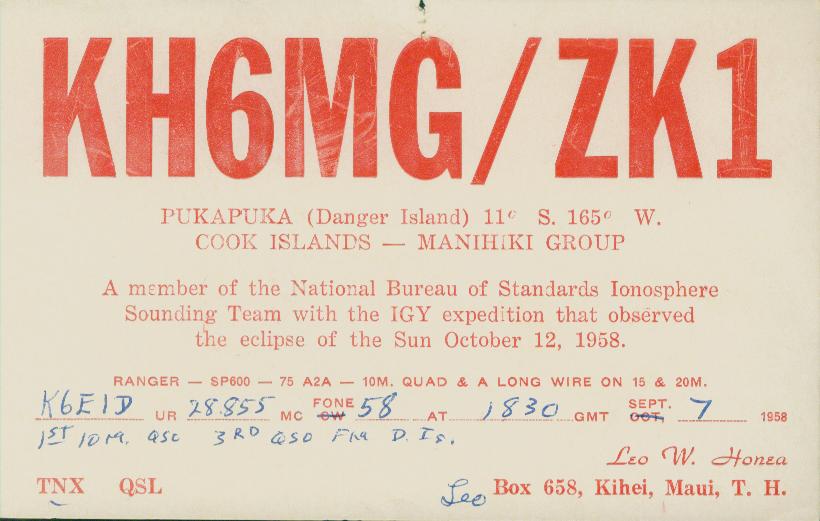

One of the first DX stations I worked was KH6MG/ZK1 on 10 meters AM. At the time I thought Danger Island was in Hawaii but it turned out it was Pukapuka in the North Cook Islands. My QSL shows I was the 3rd QSO made and the first 10 meter QSO on the expedition. Below is the story as compiled by K0MP years ago.

KH6MG/ZK1

Danger Island, 1958

I would like to take you back to a time of adventure and discovery. The time was August

13, 1958. The place was San Diego, California. At 0832 local time, the USS Point

Defiance (LSD-31) pulled slowly out of the harbor, on its way to support the International

Geophysical Year expedition to Danger Island, located in the Northern Cook Islands. On

board was my Uncle, Master Chief: F.R. Sanderlin, USN, who would be in charge of

military personnel on the island, and the military liaison with scientists from the University

of Wisconsin, California Academy of Sciences, National Bureau of Standards, Sacramento

Peak Observatory, High Altitude Observatory and Cooper Development Corporation.

You see, there would be an event on October 12, 1958, that would help scientists explain

disturbances in the ionosphere and lead the way for new discoveries in wave propagation.

The event that would take place was the total eclipse of the sun. Danger Island was selected

by the National Academy of Sciences because of "time and length of totality and the

position of the sun during totality". Some of the tests were to be as follows:

"Measurement of Lyman alpha and X -radiation from rockets flown before, during, and

after totality. Four rockets to be flown during partial phases to determine, if possible,

something about the contribution to such radiation of active solar regions. Two rockets to

be flown during totality will measure total Lyman alpha and X-radiation and will also

attempt to determine the distribution of Lyman alpha around the sun".

"Operate a vertical-incidence ionospheric sounder to determine changes in ion density as a

function of heights as the eclipse progresses". This test used a l0 KW transmitter, with an

output pulse of 50 microseconds from 1 to 5 Mhz. The antenna was a delta configuration,

400 feet transmitting and 300 feet receiving.

"Operate an interferometer, of Fabry-Paret type, to map by position angle and height, the

intensity and line profiles of the coronal lines of the Fe XXV and Ca XV".

"Undertake measurement of the intensity of the white-light corona at large distances from

the solar surface radius".

"Attempt rapid sequence photographs of the flash spectrum with high dispersion".The USS Point Defiance proceeded north, up the coast of California, to load the eight

NIKE-ASP sounding rockets that would be required for the tests. After the task was

accomplished, the ship got underway, bound for Danger Island, with stops in Hawaii and

Manihiki. It is the stop in Hawaii, that would eventually lead to a new country for many

Radio Amateurs throughout the world, because it would be the first time that the North

Cook Islands were QRV on the amateur bands. The ship docked in Pearl Harbor at 1026

local time, August 19. The ship was to load field gear and a civilian passenger. That

passenger was Leo Honea, Chief Engineer of WWVH and KH6MG (now W0GE). Leo

would be on the expedition to support the radio transmitters and communications that

would be used as part of the ionospheric tests. Along with his expedition duties, he would

operate his own personal amateur radio station. The radio equipment he took with him

consisted of a Viking Ranger transmitter, Collins 75A2 and Hammerlund SP-600 receivers,

and a home brew antenna match box.The ship proceeded on to Manihiki, to pick up a Cook Islands administrator who would

accompany the ship to the island. The Cook Islands administration would provide valuable

assistance to the expedition members as to what they could expect on Danger, Nassau and

Suwarrow Islands. The following paragraphs have been taken from a letter to the California

Academy of Sciences from the Fisheries Division, Cook Islands Administration.

"Nassau is a low island with typical atoll vegetation but has no lagoon and has a very bad

landing for small boats. This island has practically no lee in bad weather. The sea breaks

right round the reef and it is necessary to land over the reef in a shallow surf boat steered

with a long sweep."

"You will find the climate pleasant and there are no special precautions necessary against

any tropical decease. Pukapuka (Danger Island) and Nassau, however, have plenty of

mosquitoes, which make some form of fly and mosquito screening essential by day and

night. Flies are bad on most islands. There are no mosquitoes however, on Suwarrow

unless they possibly have started up from discarded water catchment areas. There is a

water catchment area on Suwarrow which is not very permanent and may be subject todamage. A small iron roof and a water tank may take care of all the water a small

expedition may need but this may be low if a native shell diving party are there."

"There are ample coconuts on all these islands, and for anyone familiar with the

subsistence food of atolls, there is ample food to live on. However, this is of course, a

relative term, and as you know, many people are unable to live on the food. All three

islands are badly overrun with rats. The rats are tame enough that they enter and feed in

houses in daytime. I would suggest that your scientific equipment is well protected from

possible rat damage. Cockroaches are common and do damage to all photographic gear."

"Australian white ant is common in Pukapuka and in Suwarrow. It should be remembered

that the coconut trees on Suwarrow are generally riddled with this white ant which renders

them very dangerous in strong winds. When setting up a camp it would be well to

remember that long tall trees often snap off with little warning when they are riddled with

white ant."

"Like most of the Cook Islands, these three islands are in the Hurricane belt, which

means in practice, that there is no local shipping between them from December until the

beginning of April. Hurricanes are not frequent in these islands and the last serious one

occurred in 1942. I was in Suwarrow at that time and had the misfortune to arrive there in

a small cutter as the sea was rising, preceding a very violent hurricane. There is another

island of Penrhyn, to the east of Suwarrow, which has a good entrance into the lagoon.

There are two villages on Penrhyn and several small stores carrying limited supplies, a

radio station in communication with Rarotonga, and this island is considered to be out of

the Hurricane belt if you should intend to stay on after December. During the hurricane in

1942, Suwarrow was completely swept by heavy seas which rose 23 feet above normal

high water. We survived by being lashed into the tops of a group of Tamanu trees. Even

after such a disastrous hurricane, it was still possible to live, or rather exist from native

subsistence foods. All fish and shell fish are safe to eat and are in ample supply."

"If your expedition has a marine biologist working on collecting fish, I doubt whether he

could find a better island anywhere for studying fish. If no people are living on the atoll,

fish are not hook shy and large tuna can be caught inside the lagoon. No classification of

the Cook Islands has ever been made and I understand from the Smithsonian Institute that

there are probably many varieties unknown to science in the area."

These are some of the conditions with which the expeditioneers had to contend with for the

next two months.

The USS Point Defiance reached Danger Island August 26, 1958. The following is from

the Navy log of. F.R Sanderlin.

"1st. day, 8/26/58 - Reconnoitered Danger Is. Group with LVT's and helicopter for

possible landing and camp site. Found landing north side Motu Katava, possible camp site.

LVT's cannot traverse living coral. No other surface presents problem within reason.

Bogged down several times, but managed to proceed unassisted. Natives very helpful,

friendly and speak English very well. Appear healthy and happy. Islands very beautiful.

Heavy lush foliage coconut palms, pandanus. Reef and lagoon paradise of marine flora and

fauna. Saw several small sharks, both outside and inside reef. One large Moray Eel.

Beaches are pink to white coral limestone sands. Walking barefooted hazardous. Will

attempt landing in morning."

Personnel landed the next day and started the long task of off loading field gear, test

equipment, generators, food, water and explosives. After a few days the ship would leave

and sail to Samoa, leaving 29 Navy/Marines and 15 scientists, including Leo Honea to fend

for themselves. The ship could not stay at the island as the lagoon had no entrance deep

enough for the ship to enter and the ocean was too deep for anchoring. The ship would

return at various times to resupply the expeditioneers with food, water and other supplies

during their stay on the island.

The Navy commenced blasting a 1200 foot long channel through the coral reef so the

small landing craft could land and resupply the expedition members. This channel also was

welcomed by the local natives of the atoll, as a safe passage from the lagoon to the open

sea. The men suffered many coral cuts which do not heal very fast in the wet environment

of the tropics. The blasting went on for quite a few days. Various types of explosives were

used to penetrate the soft coral, and then, using a drag, they moved the coral into the open

sea with an amphibious tractor. During this time a Marine master sergeant was badly

injured when a cable attached to the drag snapped. There were no doctors with the group

and Leo Honea used his amateur radio station to call for assistance in San Francisco. The

Navy doctors talked with the medical corpsman on the island regarding the first aid to be

given until the ship could come and evacuate the Marine. The sergeant recovered and was

back on the island in a few weeks.

The Navy launched two NIKE-ASP rockets for telemetry tests before the eclipse. These

rockets set a new altitude record of 158 miles. Immediately after launching the rockets,

they were informed that a very large solar flare was in progress. The scientists were able to

gather valuable, unexpected data from these test rockets.

Radio towers and antennas were erected by the Navy for communications and ionospheric

testing. Two of these antennas were for amateur radio use. One antenna was a longwire,

approximately 500 feet long erected over the lagoon, and a 10 meter, 3 element Quad. Ten

meters was very good for communications, as Solar Cycle 19 was just past its peak. Cycle

19 was the most active in the history of keeping records on sun spots. It peaked at 201 in

February of 1958, and was at 184 for most of the time of the expedition.

Leo would operate as KH6MG/ZK1 during three weeks of the expedition. He operated

CW, with some AM operation. SSB was only operated by the Navy for a world wide solar

flare alarm channel The SSB mode of operation was in its infancy with amateur radio.

Leo found that with his low power (50-75 watts), he had more contacts with CW. Leo

contacted approximately 4000 radio amateurs throughout the world. One operating

anecdote that Leo remembers is, he was listening one day to two radio amateurs talking on

10 meters. He overheard one say to the other that he wished he could work the ZKl that

was active and that he had not been able to make a contact yet. Leo broke in to the

conversation and asked "Do you really want to work the North Cook Islands?" The ham

said "Yes, I sure do!" and asked if he had a connection with the Danger Island expedition.

To which Leo answered, "Yes, its me, KH6MG/ZK1, you have just worked him!" The

new one was in the bag and there was a very surprised and happy ham! After Leo returned

to Hawaii, he did not wait for a QSL card from his contacts, he sent QSL 's to EVERY

contact!

During the two month stay on the island a visitor appeared with a group of video

technicians. He was Lowell Thomas, of television fame. Thomas was there to do a story of

the IGY expedition and of the eclipse of the sun for his television adventure and travel

show, "Odyssey". The day came for the eclipse and the sky was overcast. Only a partial

viewing was had by the expeditioneers, but most of the tests did not need the eclipse to be

viewed. Thomas reported the tests as a failure, used file footage of other islands in the

Pacific on the show and left the island. The tests were far from a failure. Scientific data

was gathered which to this day, helps us to understand the ionosphere and propagation.

After all the preparation and work, the expedition was a success. The USS Point Defiance

left with the expeditioneers on board after 58 days on the atoll, October 18, 1958, to sail

back to the United States via Pearl Harbor, with a job well done.

Leo Honea went on to have a successful career with the government as Chief Engineer of

WWVH and WWV. F .R. Sanderlin went on to a 33 year distinguished career with the

United States Navy and retired as a Commander.

I would like to thank CMDR F.R. Sanderlin, USN (ret), KB6RQO; Leo Honea, WOGE;

J. Sherwood Charlton, Ph.D., KSGOE; Frank Schottke, W2UF17; Phil Finkle , K6EID;

Tom Harrell, K8XP, without whose help and assistance this story would not be possible.

I was ten years old in 1958, and remember very clearly my Uncle leaving on this unique

adventure. I remember talking with him after he returned from the expedition, about the

adventure and of the radio operation from the island. This helped me kindle a wonder of

how radio worked, which has directly led to my 33 year involvement with amateur radio

and communications. The next time you work someone in some remote part of the world,

remember what that person had to endure, to give you that 'new one'. 1b.anks for the DXI

Bill Leahy, K0MP

Parker, Colorado

Original QSL from Danger Island. KH61MG/ZK1 is noted in the "How's DX?" column of

QST, November, 1958.Thank you to K6EID for providing the copy of the QSL.

Return

- HOME